Books

- >>The Encyclopedia of Kurt Caviezel

- >>Red Light

- >>Points of View

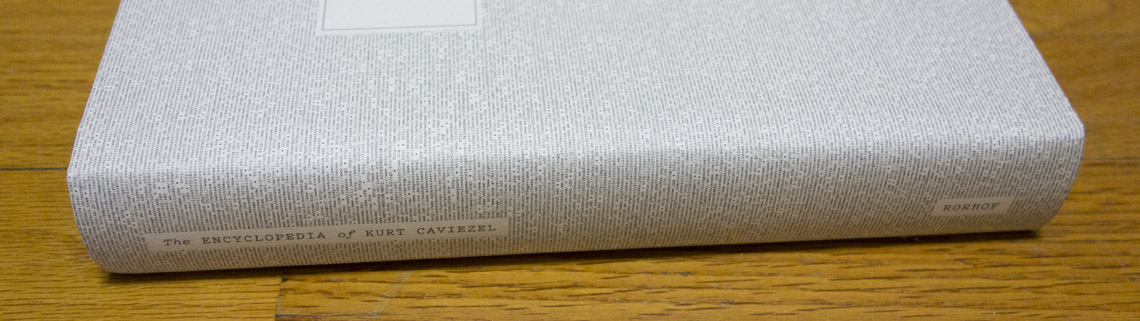

THE ENCYCLOPEDIA OF KURT CAVIEZEL

Author: Kurt Caviezel

Publisher: Rorhof, Bolzano, Italy

Foreword by Joachim Schmid

e/i/d

Format: 414 pages, hardcover, 16x24cm

First editions

Publication date: May 2015

ISBN: 978-88-909817-5-3

For the past 15 years, from his studio in Zurich, Kurt Caviezel has been monitoring 15,000 publicly accessible webcams

located all over the world.

By taking screenshots of any situation he found interesting he compiled an archive of more than 3 million images,

categorizing them for recurring patterns and subjects.

The dust jacket of the book contains all 15,000 web-links used by Kurt Caviezel to create this body of work.

From the foreword by Joachim Schmid:

Through years of camera surveillance the artist has compiled a virtually unreal amount of images, which have all been harvested from webcams. The quantity of images is of crucial importance here, because quantity (as is the case with many collections of things) at some point turns into quality. Only abundance enables the detection of recurring patterns. May the single image be just funny or banal or vacuous, in a series of similar ones it becomes a building block of knowledge. By sequencing kindred images, Caviezel makes order emerge from the torrent of images.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Review

by Loring Knoblauch

on Collector Daily, New York

While Google Street View has gotten all the fanfare as the preferred public video source for artistic mining, the lowly net-connected webcam (multiplied by likely tens of thousands) shuffles on in the overlooked background, continuously staring out at airports and weather stations, ski hills and traffic intersections, endlessly spooling up minute-by-minute footage of the mundane. While at first glance, such imagery wouldn’t appear to be a likely candidate for serendipity (most of these cameras are looking out at fixed locations, doing everyday jobs), the fact is the world is surprisingly full of accidents, coincidences, and wonders, and these cameras are inadvertently there to record them. So in an unlikely variant on the tortoise and hare story, webcam archives are turning out to be a more powerful resource than we might ever have imagined.

For the past 15 years, Kurt Caviezel has been monitoring some 15000 individual webcams all over the world, intermittently taking screenshots of his finds. (As an aside, in a meaningful feat of typographical miniaturization, every webcam address he’s been monitoring has been listed on the cover of this book in astonishingly small type.) His image archive now numbers over 3 million photographs, and if we assume that he had little or no use for 99+% of what passed through the lens of any one camera, what he’s built over time is a catalog of outliers – those fleeting moments when something unexpected happened that was worth capturing.

From there, Caviezel has imposed order on the chaos, randomness, and chance, grouping the images into subject matter categories and organizing them into typologies. Shown in alphabetical order by title, they are an encyclopedia of found oddities, a thick table of visual patterns that have emerged out of the torrential photographic noise. Not surprisingly, many of his groupings gather up observations of places and things: dams, lighthouses, observatories, windsocks, and the like; it seems that regardless of our specific place in the world, we have an innate need to endlessly watch bus stops, zoos, and swimming pools.

Of course, things get more interesting when something unexpected happens, and Caviezel is right there to prove to us that the unexpected is never actually that unusual – that exciting once-in-a-lifetime ephemeral moment has happened before somewhere else, and it’s there to be found in the archive. The moment when the sun turned black, or the single lonely cloud passed overhead, or lightning struck, or the sky turned into a painting by Caspar David Friedrich, they’re all actually repeated events, seen in Caviezel’s book as taxonomies of extremes. These unlikely repetitions pile up: the single red car, the passing FedEx truck, the chemtrail in the sky, the drifting paraglider, the ubiquitous plastic chair. With thousands of simultaneous feeds looking out on the world, it’s no wonder that some synchronicity occurs, but as seen in this rigorous format, the parallels are everywhere.

When humans enter the frame, our behavior is remarkably routinized as well. Caviezel captures both voyeuristic views of bathers, weddings, photographers at work, and surreptitious kisses, and overt displays aimed at the camera – the friendly wave, the thumbs up Yes!, the bike raised in triumph, and the bare ass shown in playful defiance of authority.

Many of the best images and visual themes are found among the categories devoted to the webcam infrastructure itself and the multitudes of problems and interruptions that can occur. The lens is routinely obscured – by snow and ice, dirt and dewdrops, fog and spiderwebs, all with unlikely beauty. Insect and birds land on the camera, walk across the lens, and let their tails hang down, as if commenting on the view behind them. Window frames, cable clutter, and scaffolding surround the camera, and worker’s hands reach up to make adjustments, and when it all goes to hell, a rainbow parade of multi-lingual error messages and fuzzy static takes over. There are even webcam selfies, where the mounted camera casts a shadow down into viewing area, in effect taking its own self portrait. Seen in groups and clusters, these commonalities are quietly endearing, a kind of wry deconstruction of the medium itself.

I imagine Caviezel’s process must be something akin to panning for gold or searching for buried treasure on a sandy beach – the hit rate for something valuable must be extremely low. This makes his encyclopedia that much more intriguing; it’s brimming with exceptions, outtakes, mistakes, and outliers, seen with an eye for humor and eccentricity and organized for clever efficiency. That these images then coalesce into definable patterns is even more surprising, or maybe not so, given the statistical laws of large numbers. In the end, it’s this back and forth thinking process about the nature of pictures (however sourced, intentional or not, original or not) that is the takeaway from Caviezel’s photobook. There’s an undeniable flood of imagery out there ready to drown us, but with the application of the right filter, suddenly that deluge is full of insights and delights.

---

Review

by Jürg M. Colberg

on Conscientious Photography Magazine, USA

If you want to understand photography, all you have to do is to go online and look at how people use it. This means you will have to see past what the pictures look like, whether, in other words, they are any good or not. We all know well what a good picture looks like (for us – this is all mostly subjective), but we don’t know nearly as well what these pictures do that we deem good or bad. Having written about this for a while now, I’ll admit that fatigue has set in at this keyboard: there are only so many times that you want to write an article about picture “manipulation” and photojournalism, say, before you realize that it’s futile for more reasons than one.

For a start, people love sticking with absurd ideas about what photographs are and what constitutes “manipulation”. But even worse is the fact that people love pretending that the use of photographs has nothing to do with how they are perceived when in fact it’s the complete opposite: photographs have almost no meanings without them being used for something (whatever that something might be).

Seen that way, what I wrote in the beginning only is the logical consequence: to a large extent photographs need to be judged not only through their form and content (which, mind you, are important enough), but also through how and where they are being used. Photographs can become good or bad through their use. Good photographs can become bad, or bad photographs can become good once the viewer understands what is at stake.

A variant of this argument is provided by The Encyclopedia of Kurt Caviezel. If the press text is to be believed, “from his studio in Zurich, Kurt Caviezel has been monitoring 15,000 publicly accessible webcams located all over the world.” It makes me shudder to think about going through 15, let alone 15,000 webcams, to look for what might present itself. But then, I’m doing the exact same thing on a large variety of Tumblrs and Instagram accounts.

So maybe I’m just as obsessed. Regardless, Caviezel compiled “an archive of more than 3 million images, categorizing them for recurring patterns and subjects,” and the book is the result of this endeavour. What it does is straightforward: there is a large list of entries, starting with “airport,” and then continuing through obvious (“bus stop”) and not obvious (“C.D. Friedrich”) ones, to finally arrive at “zoo.” For each entry, there are webcam pictures. The viewer gets 38 images of airports, say. “Costa Concordia” only contains images from one source, but the collection shows the salvage operation of the stricken ship in time.

In its simplicity and maybe degree of obviousness, The Encyclopedia of Kurt Caviezel might strike especially those embedded in academic forms of photography (curators or photography academics) as not worthy of much, if any, attention. But much like maligning the selfie as merely being an embodiment of narcissism, this would be a grave mistake (not that academics won’t happily make mistakes, while attempting to masquerade their ignorance with high-falutin jargon).

The book makes a more complex use of how the use of photography determines their meaning than one might realize at first, given that webcams are usually used for evidentiary, not encyclopedic purposes (they are in effect publicly available surveillance cameras). There is much to be said for a better, meaning: more profound engagement with those forms of photography that aren’t fully accepted into the canon.

Ultimately, the selfie is to photography today what colour photography was for “art photography” before John Szarkowski busted that silly barrier down with his William Eggleston exhibition at MoMA.

The usual argument that “there are too many pictures” today, and they’re all bad (or whatever you’ll hear from bored photographers who prefer to think of themselves as “artists”) holds no water for a large variety of reasons. For a start, if your imagination is so poor that the presence of all those photographs will prevent you from taking pictures, maybe you should look for another way to spend your time.

And as The Encyclopedia of Kurt Caviezel demonstrates, to deny oneself of the sheer enjoyment that can be had so easily from engaging with the crazy world of photography generated by essentially all of us strikes me as, well, nuts. If you just start looking at what you can see in pictures, and what people do with them these days, you will be amazed.

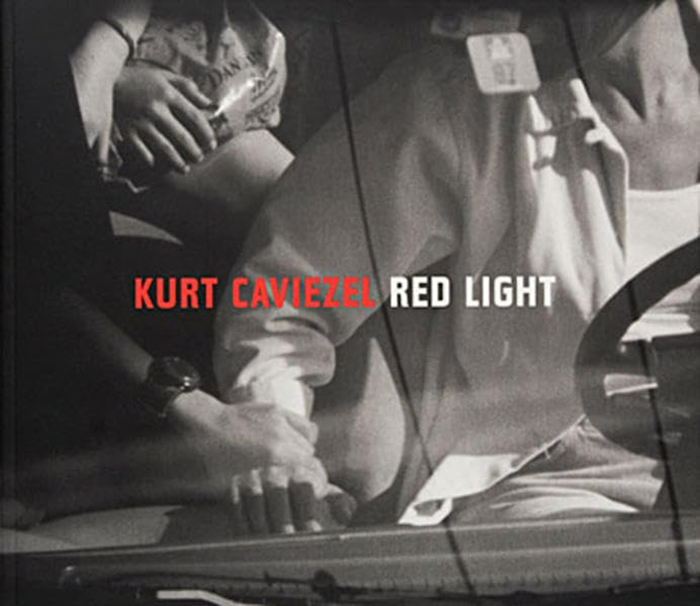

KURT CAVIEZEL, RED LIGHT

Author: Kurt Caviezel

Editon Patrick Frey, Zurich

Softcover, 276 pages

252 b/w images

21 x 24 cm

Publication date: 2000

ISBN: 978-3-905509-21-2

.jpg)

During the summer months of 1997, Kurt Caviezel photographs, through his window, the interiors of cars stopping

at the red light outside his apartment on a busy Zurich intersection.

The view through the 1000 mm tele lens, double-glazed window pane and curved car screen is obstructed by reflected light,

mirrorings and slight distortions, acquiring a certain atmospheric distance in its surreptitious encroachment while seeming

detached, objective, interested only in passing.

The slanted view from above catches a spectacularly commonplace interface between intimacy and public view.

Red Light is fragments of sitting bodies and snatches of expressive body language, a complex, fascinating ballet of gestures

and hinted-at movements between steering-wheel and safety-belt, as well as a fleetingly captured inventory of details of car

interiors and pieces of clothing, with a wealth of expressive signs and patterns.

Red Light is a stream of information on which the viewer glides along, pouring over the detail of a purse embossed with a heart

pattern here, and musing on the assimilation of individualism and anonymity there.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)

Review

by Jean Dykstra

in Art on Paper, New York

There's plenty of action, in Kurt Caviezel's Red Light (Zürich, Berlin, NewYork, Scalo, 2000, $45). In the tradition (sort of) of Walker Evans and, more recently, Luc Delahaye, this is the Swiss contribution to photographs of anonymous passengers.

Rather than smuggling his camera onto the subway, Caviezel stayed in his apartment and, using a 100mm telephoto lens, photographed the occupants of cars stopped at a red light. These are grainy, partial glimpses, yet Caviezel manages to catch a sometimes comic accumulation of fleeting gestures within these seemingly private cocoons.

He has grouped the images loosely, but thematically: drivers talking on the phone, appeasing children, eating; animals (from living passengers to faux zebra seat covers); people arguing, preening in rear-view mirrors, and (of course) picking their noses. Drivers and passengers hold hands, kiss, smoke, gesticulate, read (!).

But within this remarkable variety, it's actually the repetition of gesture that stands out:

the number of people who scratch with intense concentration at their arms, for instance, or yawn with abandon while waiting for the light to change are part of his rough typology of behind-the-wheel behavior. And we, sheepishly, recognize ourselves in these pictures of anonymous strangers.

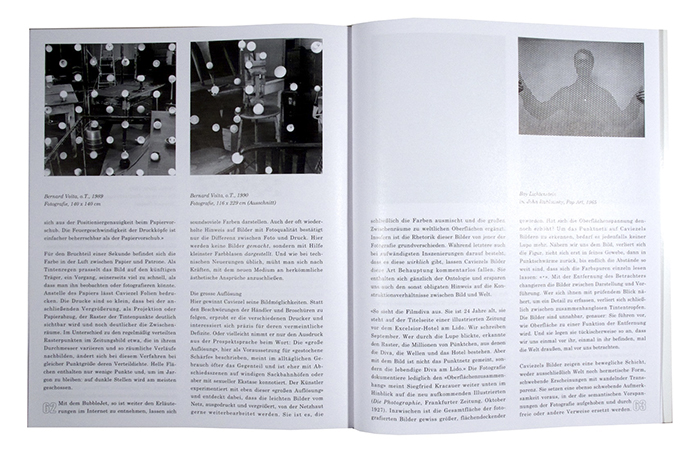

POINTS OF VIEW

Autor: Kurt Caviezel

Hrg. Ulrich Binder und Bündner Kunstmuseum Chur

Texte: Beat Stutzer und Ulrich Binder

Gestaltung: Ulrich Binder

Edition Howeg, Zürich 2002